Esther Dyson on Investing in Insurance, Mapping, Mental Health, and Telehealth

/LDV Capital invests in people building businesses powered by visual technologies. We thrive on collaborating with deep tech teams leveraging computer vision, machine learning, and artificial intelligence to analyze visual data. We are the only venture capital firm with this thesis. We regularly host Vision events – check out when the next one is scheduled.

Our Women Leading Visual Tech series is here to showcase the leading women whose work in visual tech is reshaping business and society.

Esther Dyson is an investor, journalist, author, businesswoman, commentator, and philanthropist. She is a leading angel investor focused on healthcare, open government, digital technology, biotechnology, logistics, and outer space. Currently, she is a full-time executive founder of Wellville, a ten-year project (ending in 2024) to show the long-term value, in both equity and resilience, of investing in health for all.

She is a board member of Yandex (YNDX) and was an early investor in such notable startups as 23andMe (former board member), Evernote (former board member), Flickr, Mashery, Medstory, Omada Health, and Square. Overall, she is fascinated by new business models, new technologies, and new markets (both economically and politically).

From October 2008 to March of 2009, she lived in Star City outside Moscow, Russia, training as a backup cosmonaut. Apart from this brief sabbatical, she is an active board member for a variety of startups.

She has a BA in economics from Harvard and was the founding chairman of ICANN from 1998 to 2000. Esther wrote the bestselling, widely translated book Release 2.0: A Design for Living in the Digital Age.

LDV Capital’s Abigail Hunter-Syed spoke with Esther about investing in visual technology companies, genetics, AI-powered MRI-based cancer screenings, and much more! (Note: After five years with LDV Capital, Abby decided to leave LDV to take a corporate role with fewer responsibilities that will allow her to have more time to focus on her young kids during these crazy times.)

Abby: Esther, thank you for joining me today to chat about visual technologies and investing! You have a variety of different roles that you've played throughout your career, everything from an investor to cosmonaut in your background. For people who are just tuning in, how would you describe what you do?

Esther: I never take a job for which I'm already qualified, and I do things because I think I'll learn something and also ideally, produce something of value.

I was a good student in high school, because I wanted to get out, and I went to college two years early. In college, I had a wonderful time, wrote for the Harvard Crimson, never went to class, and it was great. I learned how to be a teenager, and then I started my education about two years after I finished college when I got a job as a fact-checker for Forbes Magazine. If you're going to check facts, you need to know your stuff. I majored in economics and never learned much, but I learned a lot about business at Forbes. Then I was on Wall Street for five years.

Then for 25 years, with amazing timing, I had a newsletter that covered the emergence of the personal computer. We also had a conference called PC Forum, Personal Computer Forum that ended up, 25 years later, being called the Platforms for Communication Forum, still PC Forum, about the internet and social networks. In the beginning, we had Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, by the end we had Reid Hoffman, Mark Zuckerberg, and Larry Page as speakers. Then I sold the business, became an Angel Investor, got more and more interested in healthcare.

I took six months off to train as a cosmonaut in 2008-2009, and then started leaning into the healthcare side and began to ask the fundamental question, which is:

Why are we spending so much money fixing things with people who shouldn't have been sick in the first place?

In 2014, I started something called Wellville which is a 10-year-project to produce resilience and equity in five small communities around the US. It's kind of a model of what we should do after COVID-19. Let's invest in children, health, resilience, and equity so that the next time something bad happens, it doesn't crumble our society as badly as it is doing right now.

Abby: I think resilience is the keyword. What we've realized more than ever with this pandemic is that we are not resilient. If so many businesses and opportunities can crumble from a month of a shutdown. What brilliance or resilience have we built into those businesses?

Esther: Or the people undergoing them... I think the aftereffect of post-trauma stress is going to be one of the worst aspects of all of this. Everything we can do now is to give children a more secure present so that they have a more resilient future.

Abby: What inspired you to go down this path?

Michelle Preston (a securities analyst), Bill Gates, and Esther Dyson at PC Forum back in the 80s © Ann Yow-Dyson

Esther: It was curiosity. The thing I hated about college was learning stuff and repeating it. Once I started being a reporter, my job was to find out new stuff, and that was fun. The internet, the personal computer, it started with Word Processors. When I was working at Forbes I had a typewriter. That intrigued me so I went to places where I could learn more about it. That's why I joined the board of 23andMe. It's why I did cosmonaut training in Russia... In each case it was, "I think this is interesting, and I know if I go there or do this, or join this board, then I'll become an expert." I also went to Russia for the first time in 1989 for the same reason. These were all fascinating things that intrigued me, but the one where I felt there was a moral dimension was this health issue. I keep asking myself:

Why are we failing to bring up the next generation in a way that will guarantee them a much better future?

Abby: It's interesting because it seems like in the five communities that you guys selected to operate in, and work with, you selected different things to work on. It seems like they're tailored specifically to those communities, more so than just being a blanket statement like, "This is how we're going to come in and improve your health."

Esther: We selected them but it wasn't, "Here's a nice white lady from New York and she's going to give you some tech to do things." It was very different, we put out a call for applications. The first thing I did, having learned from Silicon Valley, how some people destroy the things they love. I hired a CEO, and my CEO came from Sigma and he knew about public health, he understood the institutions that we were going to be dealing with.

Together, we put out this call for applications. You had to be a community, ultimately under 200,000 people, you had to have some kind of cross-sector collaborative that was applying, and you had to be self-contained. The idea was we weren't going to go in and work on a subset of the population, we were going to help the whole community to become healthier for all its members which meant equity, in other words, don't just make the rich people healthier and then say you've increased the average. But bring the bottom half up. 42 communities applied to our great amazement. And this is not just, "Send us a letter," it was quite a detailed application.

We read them all and picked 10 of the communities to visit. Then what we were looking for was not, "The 10 best," in fact the very best one we did not select because they were too good. We wanted to make a difference, we didn't want just to say, "Oh, these are great, we picked them." We wanted all kinds of diversity, and geography, and the institutions within the populations. We got five very different places, and then in terms of what's going on in each community, again, we're not coming in with programs for them. They all have some notion of what they want to fix, and our job is to coach the ones that are going to be effective, and even more effective with coaching.

In each community, we're not necessarily working... there's turnover among people, there's even turnover among organizations but what we're trying to do, in terms of the people in the community, we want to increase equity. But in terms of the institutions, we want to help the best ones become better, and grow and collaborate because that's where you get the leverage.

It varies from community to community, the kinds of organizations we're working with, and the kinds of problems they're addressing but they're all in one form or another, offshoots of poverty, and racism, and just inadequate services to people.

You asked me if there was an origin story, and the one for Wellville goes back to this guy Charlie Silver who had a website called RealAge that I wrote about for my newsletter.

He created a website where you answer questions less about your healthcare and more about, "Do you have a dog? Do you have a partner? Do you eat right? Do you sleep well?" And it tells you what your "real age" is versus your actual age. He ended up selling that to Hertz, which then sold it to Sharecare, but what was interesting about Charlie, is who he sold his previous company to, and that was Jiffy Lube – the oil change people – and it's like, "Oh, yes what we do with our cars, we should do with ourselves. Keep the thing in good running condition, it's an investment." To me, that's always been the metaphor: invest in your health, don't rent it.

Abby: It seems like there's a major convergence for you between the science and the physics that you grew up around, and the tech and internet world that you embarked on first in your career. Can you talk a little bit more about this idea that you have that people see you kill what they love, do you have any example or story that you think about in your mind?

Esther: Here’s an example of Elon Musk. There are two Elon Musks. There's the SpaceX Elon Musk. This company is well run, it's exciting and doing risky stuff, but it's fundamentally an organization that works. It's sensible and successful. Then there's Elon Musk at Tesla, where he runs it himself and he's continually doing crazy things and putting the entire operation at risk because he doesn't have someone there telling, "Dude, just sit in your chair and be quiet."

It's important to have somebody who will tell me as the founder, "Esther, that's a dumb idea." Wellville was originally called HICCup as in the Health Initiative Coordinating Council. I thought “HICCup” was a clever name, and it was, but it was also a terrible name for a company in the healthcare space. That was the very first thing our CEO said to me and I replied, "Okay. Come up with something better," and he did.

Good companies are run by teams, and good founders want the company to succeed even if it means they shouldn't be running it.

At EDventure Holdings, I also had a CEO who would tell me if I was being obnoxious, or foolish, and that's good.

You look at the world around you and you see important people making bad decisions because no one dares to tell them the truth. It's scary.

Abby: I probably would attribute a lot of that to you too, because I think that in a lot of ways it's not just about the willingness of other people to bring things up, or to be that check and balance upon you, but also the willingness of you to listen, which can be a factor. Is this a major filtering point for you when you're looking at an investment at an early-stage team?

Esther: One of the worst things you can say if you want me to invest is, "I've always wanted to be CEO." Or, " I want to be a billionaire." That is not the right motivation, it's, "I've always wanted to solve this problem. I think I have a solution. If this solution turns out to be wrong, we'll pivot. If I turn out not to be a good CEO, we'll bring in a good CEO to make this thing work." That's what I want to hear.

Abby: You invested in a company called Ezra that we're co-investors in, that's using MRI to detect 13 different cancers in women, and 11 in men. Can you give an example of how you found a conviction for Ezra, and Emi and Diego, the co-founders of Ezra?

Esther: I knew Emi from his previous company “Brainient” which I was a small investor in. It was video advertising. I am not a big fan of advertising or video, but I like Emi. He sold Brainient, and then was looking for something new to do. He decided he wanted to do AI for cancer detection. He knew nothing about it, which was perfect because he was willing to learn. Watching him learn, find people who knew more than he did, look for radiologists, that is what made me fall in love with him and the company.

Precisely because he knew nothing, he was extremely open to learning and finding the best people.

Abby: I guess it's a holy grail for us when we find something that we believe in so strongly from a value perspective. There’s value in being able to screen yourself before you have cancer to understand when you got the earliest signs of it. Especially if you're carrying a BRCA gene or something similar. Then being able to marry that with such a fantastic founding team of people, who are working hard and listening, and are iterative and collaborative with all the people that they surround themselves with.

Esther: There's another cool thing: the original focus was prostate cancer because that's not paid for by insurance, and we're getting more and more formalized, and recognized by the FDA. Originally it was, "We'll get all these rich guys on the Upper East Side because they can pay.” We did, but we also got truckers from Staten Island, and...

Abby: My dad.

Esther: We got a lot of men who simply weren't part of the regular healthcare system. Men don't want to pay for healthcare, they might have a high deductible, and they don't want to go to a doctor and have a nurse look at them and say, "I can tell you're pre-diabetic, you're fat. You should stop smoking." They would say, "Lady, I know that, leave me alone." But then something turns up and they need help, and Ezra's a cost-effective solution in that way versus eating up your deductible.

We're still not what I would consider my core, which is underserved populations, but we're not just helping the idle rich.

As you can imagine, I've done the full-body scan. And three years from now if there's a lump you can see a timeline.

Abby: Absolutely. If I think about the reason my dad went and did it is he got an elevated PSA level from the test. As a man who's retired, and doesn't want to pay a ton for healthcare because he thinks of himself as incredibly healthy, he's got terrible coverage. It ended up being the cost-effective and less painful solution for him to be able to go in and get a scan than it would have been if he went in for a biopsy. Luckily, It turned out that he didn't need a biopsy. Another lesson that we think is important from this is starting with something specific and then expanding your offerings to reach that larger audience, or that larger goal that you have, vision for your company.

Esther: It's worth noting that the PSA gives a lot of false positives, and then the biopsy can often give you a false negative because unless you hit the right part of the prostate, you just miss it. It's a problem with our healthcare system. The MRI is a much better way to do it and it should be paid for by insurance, and with luck, Ezra can help prove that.

Abby: At least now you can get it covered by your HSA, in case anybody's interested. Many other companies that you're investing in are leveraging visual technologies to succeed. One of them is 23andMe. We think of it as a company powered by visual technology because it uses Next Generation Sequencing – a fluorescent imaging technology – to understand the genetic sequencing of an individual. The Human Genome Project took around 20 years, and over a billion dollars to sequence a human genome. Now, 23andMe can do it for you in about two weeks once you send in a sample, is that right?

Esther: It's slightly more complicated than that, but yes.

Last week, I discovered that I have the protective neanderthal gene against having an overreaction to COVID-19. It's on chromosome three. Over time, it’s increasingly useful.

There's a difference between knowing what causes something, and knowing how to fix it but knowing what causes it is a good step in the right direction.

Abby: I saw that on your Twitter. I think it opens up a lot of questions about what's the next step for all of this genetics stuff. Now we can get a readout, but what does it mean, or how does it change everything in the long run?

Esther: In the middle ages, people said “if you looked in a mirror you would see the devil behind you”. Now people have the same feeling about their genome, equally without rational reason, that it's scary. It shows you risk but it doesn't show you a diagnosis or an outcome.

I have a theory that when people look at their genome they just add everything up. They think "I've got this risk and that risk". They have a 400% chance of dying in their head.

I like to tell people that by going into space you can reduce your risk of dying of breast cancer. Do you know how?

Abby: From my understanding, it deactivates an aspect of your genome, is that correct?

Esther: No. If you're 25% more likely to die by going into space, of something that happens in space, then your risk of dying of breast cancer is reduced by 25%.

What I tell people is, "Imagine this pie chart of how you're going to die," and it takes out the subtleties of dying of, and dying with. It's 100%, and there's this little, little sliver of blue which is that for some reason you don't die. But otherwise, your chances of dying are 100%.

Everything you hear about you've got to fit into this chart, it's not going to make your chances of dying increase. It makes it more finite.

To me, that's one of the most important visualizations around genetics: no matter what risk you have, your ultimate risk of dying is still just 100%

If you take a big slice out for dying in space, the other bits get contracted.

Abby: The other day, we had a conversation with the women in my family because it turns out that my grandma had some type of gene that starts to degrade your nerves down in your legs, it leads to you being unable to walk later in life. Half of the women in my family say "Yes, I want to go get sequenced to see if I have this risk factor, or if it's even there." We don't know if it's activated or not, we just know that it's there. The other half says, "I don't want to know, there's no reason for me to know. I'm either going to have it or I'm not." It was an interesting discussion between us about, "Should we go? Should we not go? What's the benefit of knowing versus not?" There are still many conversation points or controversies, about what those genes mean.

Esther: So what about you?

Abby: I would rather know because I would like to make sure that my family is prepared for it, or I put in place the things that can make it easier for me to live longer at home, or spend more time with my kids, and do as much preventative work on it as I can if I seem to have the gene or the gene seems to be expressing itself once I hit 40.

Esther: Do you or...?

Abby: I don't know yet, we have to go get sequenced.

Esther: Oh, okay. I have an APOE4 for Alzheimer's. In the end, it means to stay as healthy as you can, which I've been doing anyway, and it hasn't changed my life much. It's different from “my risk went from 7% to 13%”. It's not a death sentence, it's a risk. This goes back to all the Wellville stuff – it's not your genes, it's your behavior and the circumstances in which you grow up that have a much bigger difference.

Abby: Thinking about these kinds of things from a health perspective, and also a bunch of other visual tech companies that you've invested in... Do you have any hypothesis at the moment, where the world is going in terms of visual content?

Esther: My parents are scientists, I love graphs and charts. It drives me crazy when I see a graph that doesn't have zero at the bottom. I think we're getting better at explaining stuff visually and with charts.

I have five different sleep monitors and I've got an additional electro stimulation device I use at night. I've got a deal with somebody and I've given him the password to my five sleep devices and said, "Look, you can have all my data, I want you to put them into a single graph so that I can see," because they all agree, "you slept good, or you slept bad," but they don't agree on any of the details. I would love to see them all on the same chart, but we need so much standardization... The AI can figure stuff out, but you want to be able to see the impact.

If I ran the world I would give every second grader a continuous glucose monitor, so they could see the impact of the food they eat, and how much they exercise, and everything else. I want them to be able to see it, like, "Oh, I ate the banana, and it went up. I didn't have any lunch and this is what happened."

A good chart will always explain something quantitative, better than just a bunch of words.

Abby: We were recently talking to a company in the agricultural space. They're looking at meatpacking plants, and the spatial distancing from all the different COVID outbreaks, and what the interactive nature between the two is. The person who did it ended up saying, "That was our ah-ha moment – the moment that we took all this data, put it on a map and we could see it.”

Esther: One of the very few good impacts of COVID-19 has been a lot more charts. People are getting much better at using data, and showing timelines, and understanding the lags. First, you get the cases, then you get the deaths, then you get the herd immunity, we hope...

The data don't lie, but they also don't tell a story until you see them in a visualization like that.

Abby: If you had a recommendation for women who are starting out investing right now, what would you tell them? When is the right time to start investing?

Esther: It's like a question “when is the right time to go to college?” or “When is the right time to stop learning, and start earning?”. It varies. If you're talking about angel investing, the right time is when you have enough money to diversify, because fundamentally angel investing is an educational activity. For example, you learn a ton by making 10 investments, and if you're lucky, your education will be paid for by one or two of those investments. You'll learn a ton from the eight ones that failed. If you're unlucky, all 10 will fail, but if all 10 work out, you probably won't learn much because you won't understand what can go wrong.

Abby: You get more lessons from losses than from the wins.

Esther: Yes. And the losses are... mistakes in some sense, but they are the cost that you pay for the learning and they're the cost that you pay for the return on the one or two that work. If you can’t do 10 or more, your chances of losing it all are quite high. It doesn't mean just spray the money around.

I have a few investments where the first one failed, and I invested in a person the second time and it worked. With Emi at Ezra, they both worked, but you can learn a lot from your first failed investment, both as an investor or as a CEO. There are ones where the founders did not come up with another idea, or concept, but I don't regret the first investment because I believed in what they were doing, I believed in the people and they're still friends. Invest in things you love, and then you'll get the education.

Abby: Are there any kinds of visual tech companies, or companies in general at the moment, that get you excited, and that you're looking to invest in right now?

Esther: The companies I'm mostly focused on are in the mental health and telehealth space. I'm also in a couple of logistics companies. I'm a big fan of insurance companies because to understand incentives, and risk you need good visualizations. I'm an investor in Openwater which is not visualization, but actual scanning.

I love maps. One of the companies I'm investing in right now is a trucking insurance company where the founder’s first company was a map company.

Take a look at our LDV Capital Insights reports that relate sectors that Esther is focusing her investing these days.

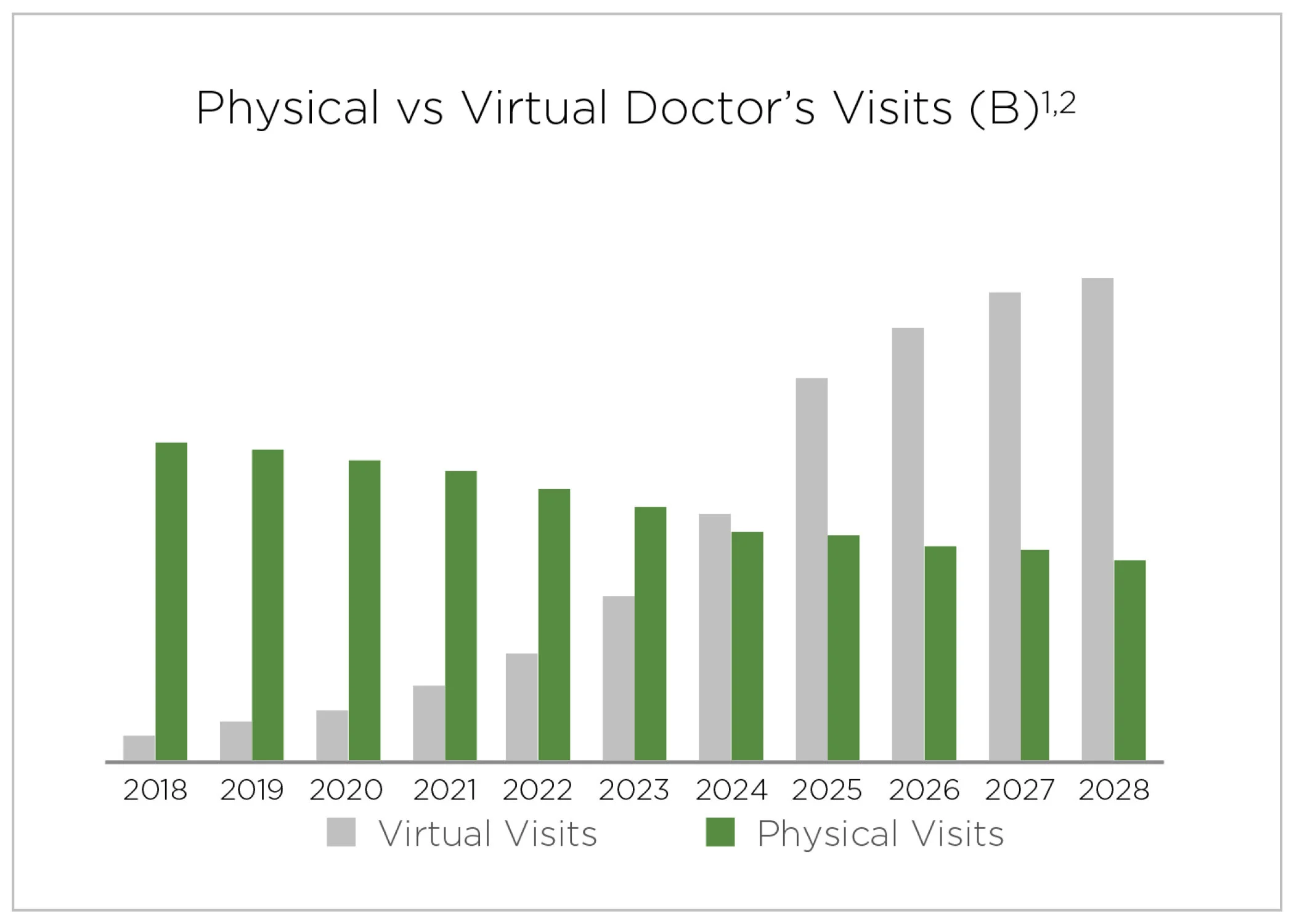

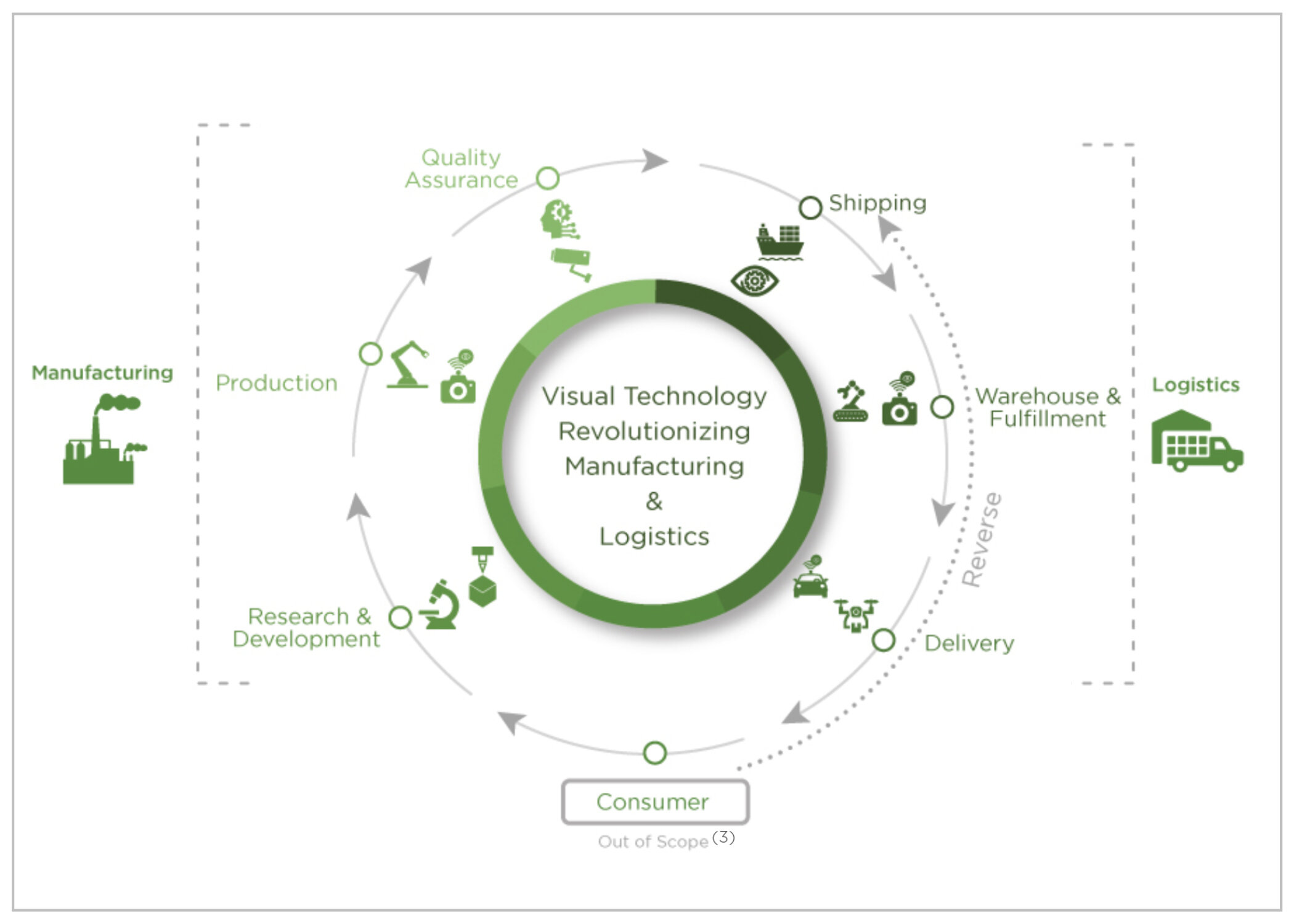

Abby: We've looked at a variety of those spaces, for instance, telehealth. A couple of years ago, we wrote a report and we projected that by 2024, the number of virtual visits would overcome the number of physical visits that you pay to a doctor, and we've already surpassed that within this pandemic. We think that that's going to continue to go up as well, I agree with you, telehealth is a huge thing at the moment. Then we've looked at the logistics space, too, and with everything that's happening around automation.

Esther: Automation – yes but also the whole notion of slack versus sufficiency. I find fascinating dynamic scheduling, dynamic pricing, and the impact of 3D printing – not on mass production, but short term, just in time inventory management.

Abby: My last question for you: if computers didn't exist, what would your career choice have been?

Esther: Space travel.

My career goal in college was to be the Moscow bureau chief of the New York Times. Never got around to it, I had more interesting things to do but you never know.

Abby: It's been fantastic chatting with you! We appreciate you taking the time and sharing your insights and guidance on everything from investing to the holistic view of healthcare, and how we can be improving things around the globe, hopefully, for everybody who lives.

A video version of this interview is available below: