Lessons from Commercializing AI Research, Starting Deep Tech Businesses & Building AI Products At Fortune 100 Companies

/Interview with Clément Farabet, VP of Research at DeepMind

Clément Farabet received his Ph.D. from University Paris-Est while a visiting researcher at NYU. He was co-founder & CTO of Madbits.

The Madbits team built visual intelligence technology that automatically understands, organizes and extracts relevant information from raw media. Understanding the content of an image, whether or not there are tags associated with that image, is a complex challenge. They developed their technology based on deep learning, an approach to statistical machine learning that involves stacking simple projections to form powerful hierarchical models of a signal. In 2014, Madbits was sold to Twitter, where Clément then co-founded and led Twitter Cortex for almost 3 years.

Clément was VP of AI & AV Infrastructure at NVIDIA, where he was building the foundations of NVIDIA’s AI, AV and Data Science platforms, MagLev and RAPIDS.

Most recently, Clément joined DeepMind to help their extraordinary team continue to lead in their quest to build artificial general intelligence (AGI).

If you missed our 9th Annual LDV Vision Summit, this is your chance to watch the video or read this shortened & lightly edited transcript. You might also want to check out our 5-question interview with Clement that was published leading up to the Summit along with 13 other interviews.

Evan: When you were a Ph.D. student, what did you think you were going to be doing in 10 years and has it happened the way you thought?

Clément: Some 10-15 years ago when I started working towards my Ph.D, I joined a small crew of people worldwide who were obsessed with neural networks. We thought that neural networks would be the path to AGI.

Back then, we didn't use the term AGI, but we used AI in general, and there were 30-40 people worldwide who thought that scaling these neural nets would be a way to solve general-purpose intelligence problems. Fast-forward 10 years from that time, I was convinced that I would've contributed some key pieces to this AI puzzle. Did it pan out as planned? I'm not sure. I contributed some important things to a few large companies. We still have a long way to go, but every year is getting more and more exciting on this exponential path to solving this problem. It turns out that neural nets were indeed a key part of the puzzle. I'm happy about that!

Evan: How long might something happen if we're right or if we're wrong? It sounds like you think it might have happened sooner, or do you think it's happening slower or faster than you expected when you were a researcher?

Clément: It's all happening faster than I expected. In 2008-2010, a lot of the projects I used to work on were to build hardware accelerators for neural nets because we all knew that compute and the availability of great training data were the key things to scale those neural nets. It turns out that these things are still true and relevant today.

Back then, building this sort of custom computer was key to making any form of progress. Then NVIDIA took over this entire industry and they leaped us forward by so much! It is almost like a time machine. We would've waited for maybe 20 years to have enough compute and enough data to solve these problems. Everything happened way faster!

In the past couple of years, we are realizing that by scaling those models on pure text input, we can learn extremely deep models of the world, which is surprising to many. It's still not completely solved. There are many other things to figure out, but it's happening faster by at least 10 years, from my perspective.

Evan: That's great because I frequently feel it takes longer than expected. I'd rather it happen faster because then there's more time for iteration. This also means exciting things and that thrills me! How did you decide to start Madbits instead of joining a big company?

Clément: Back then I couldn't decide whether I was going to be a researcher and dedicate my life to researching some of these deep questions and figuring out these deep problems, or I was going to be an entrepreneur and start companies and figure out a way to build products with that great technology and bring that to the market. I have a hyperactive nature, and so I like to be working on many things at once. It's hard to be a researcher when you have this mindset because it requires more focus on doing one thing at a time and doing it really in-depth.

During my Ph.D., I started two other software companies before Madbits. Madbits was the time when everything started to make sense to me. I knew that we needed to continue investing in deep tech, but some large companies were going to do that better than a startup.

It was also the perfect timing for these technologies, especially visual neural networks because most of the large companies did not have any technology to look at visual content. Images & videos were largely invisible to them. Companies like Twitter, Apple, and even Facebook back then were dealing with metadata. It was the perfect timing to build a startup that would build a visual search engine. I got excited about that.

We spent two years building the core technology, and we had one of the first products – visual search. We indexed most of the social media streams, which back then were public.

Evan: Where was that office?

Clément: On the Lower East Side.

Evan: There were five of you in a small office for two.

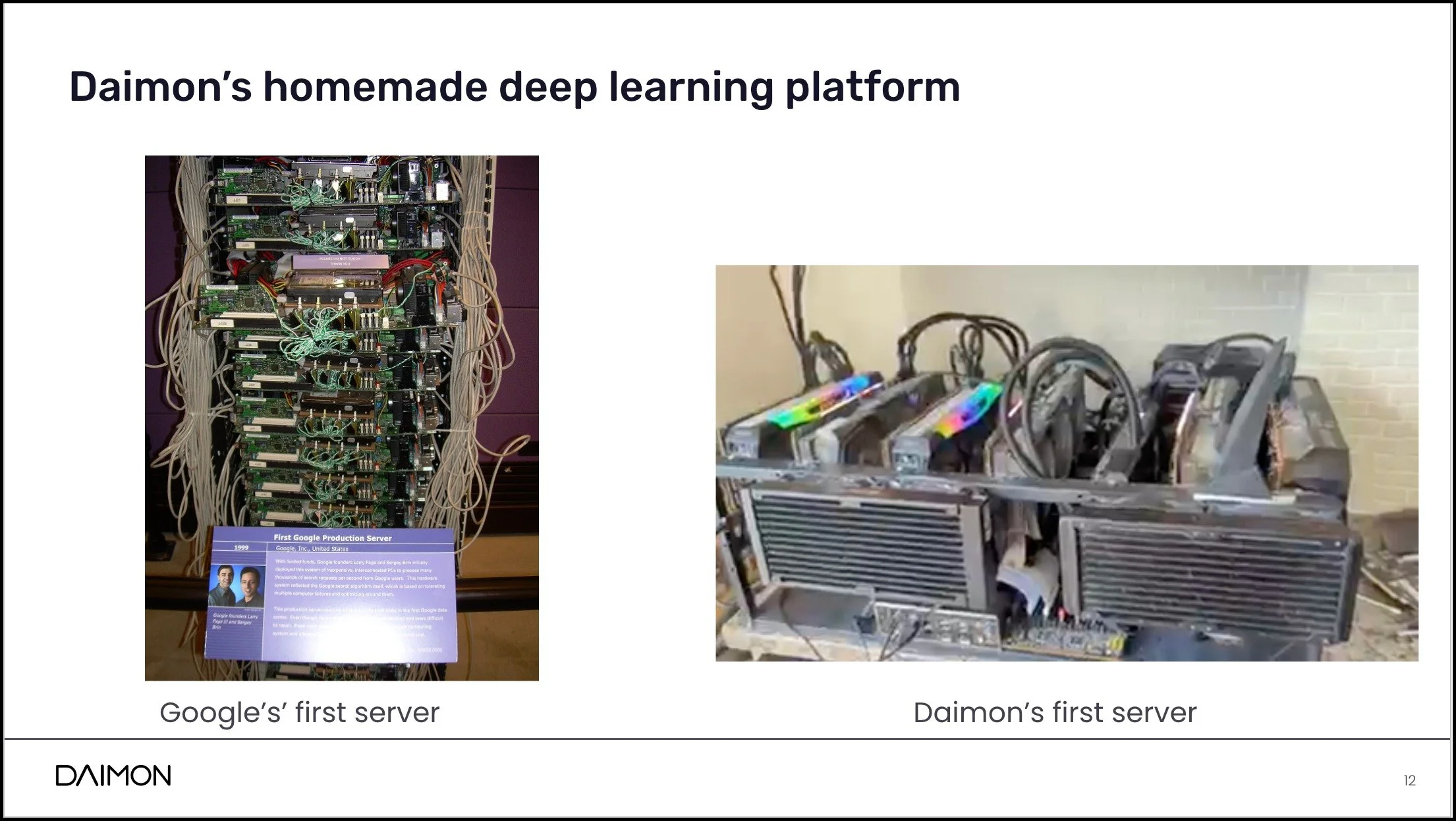

Slide from Ryan Benmalek’s keynote presentation at our 9th Annual LDV Vision Summit demonstrating custom-built GPU rigs.

Clément: That's right. I just watched the previous talk, “The Next Generation of Large Language Model Chatbot with Human-Like Empathy”, which was great, and looking at this sort of custom-built GPU rigs… we had the same thing! I assembled the entire GPU rig we had. Everything was NVIDIA-based. It was in the back office of that small apartment building, and we took down the electricity for the entire building at least 4-5 times in the span of 6 months.

Evan: When I was an entrepreneur, it was pre-cloud computing. We were managing millions of images of which we were training or running the servers in the office before we went to screw them into the co-location facility. There were only two of us. That's part of every startup.

Clément: Exactly. To your previous question, that's what I love as well. As an entrepreneur, you start a company, you are going to be doing everything. You're literally going to be cleaning the floor of that apartment yourself.

Evan: I was the head sweeper for the hallway! What was Madbits and why did you sell it to Twitter?

Clément: Madbits was a visual search engine company, and we never got it to the market. It remained a closed beta. This thing was so impressive! You could search through an extremely large dataset of visual content, images, videos, and your personal library. We would index your Apple photos. We would index the web and social media. We showcased our working prototype to a few executives, 5-6 main companies in Silicon Valley. We heard, “We want to acquire you, we need to have that as part of our backend,” and that's what happened.

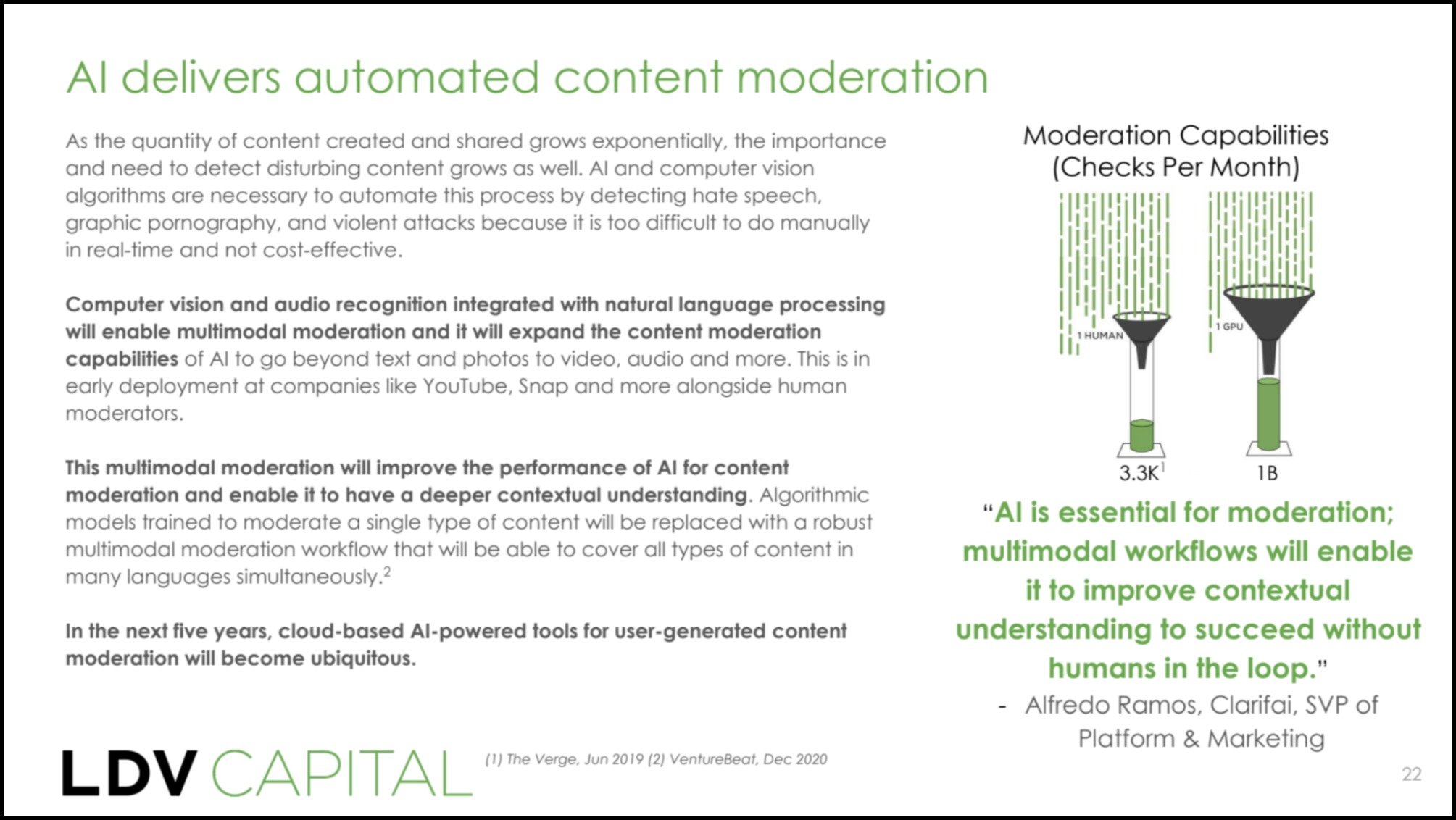

Evan: When you joined Twitter, you built this team called Cortex Core, and I found an article titled, “Twitter's new AI recognizes porn, so you don't have to”. Tell me how that relates and is that what you were hoping they were going to publish? Was that what you were doing?

Clément: That title is absolute click-bait and we found that when it got published. I remember having an interview, talking about these technologies and being excited about what we were building. Then this thing came out and I was like, “Come on…”.

Evan: Obviously, what you were building is much more powerful than that, but it was part of what you were helping to manage that content moderation, right?

In our 2021 LDV Insights report, “Content & the Metaverse are Powered by Visual Tech”, we examined the top visual tech trends that are reshaping digital creation and identified the unique business opportunities to support creation over the next 5 years.

Clément: Click-bait title aside, the article was spot on. Large-scale social media platforms have incredible moderation challenges, mostly because a lot of them decided to centralize content moderation. Platforms like Twitter or Facebook are built around this idea that there would be some centralized entity that would decide what can be showcased in public spaces versus what needs to be down-ranked.

Based on that, you need to rely on those types of algorithms to look into content and help filter out things that would make no sense for the greater audience. These problems were gnarly and not so great to look at, but it felt good to solve them because they helped make these platforms safer spaces. I'm glad we did it. The click-bait part was not so great though.

Evan: So you're at Twitter, which is a big company, and then how'd you make that decision of joining NVIDIA, another big company?

Clément: I love what we built at Twitter but this company fundamentally lacked technical leadership and vision in terms of what to do next. Around that time, I met Jensen Huang, the co-founder of NVIDIA, and we started having long chats around what is the future of AI. It was 6-7 years ago, and we were describing what's happening today, which is mind-blowing! Jensen always had this tremendous ability to see the future, at least on some kind of 5-10 year horizon and position all his investments so that they would become the platform for that. He succeeded at that. It was a brilliant strategy and alignment with what the industry needed. I got excited about joining him and building something that was more fundamental than my work at Twitter. Cortex was the platform for AI at Twitter but was like a side product. At NVIDIA, I had the opportunity to go build that for the entire industry and apply that to deeper technology problems like self-driving cars, for instance.

Evan: As far as challenge and opportunity, that’s huge! Was it what you expected?

Clément: Partly, yes. NVIDIA is at the absolute center of this entire technology revolution we're going through. You can look at every startup that's doing generative AI or trying to apply AI to any of what we're doing today, most likely they are consuming NVIDIA technology at one level of the stack.

I expected to start building a consumer-facing AI platform for NVIDIA. Very rapidly, it became much more important for us to build an internal platform to support new initiatives like self-driving cars, genomics and so on. I went back to building background infrastructure, and it was great. We built something tremendous and that is meant to continue scaling in the next years to come. I’m proud of that.

Clément spoke about delivering computer vision and AI to the edge at our 4th Annual LDV Vision Summit in 2017.

I wanted to go back to the product and be more connected to the applications we're building and how AGI is coming together as a whole. That's what led me to move on and explore new opportunities. NVIDIA is a fantastic company and I wish good luck to anybody who is trying to compete with them.

Evan: When you announced leaving NVIDIA, there was an in-between period, and I thought you might start a new company, but you decided to join DeepMind. Let’s talk about this transition. Each time a friend, a brilliant person goes in and out of big companies or thinks about starting a new company, it's always interesting to know or to learn how each of them makes decisions. It seems like you love both the startup world and the big companies. But Twitter, NVIDIA and DeepMind, it's three big companies in a row, right?

Clément: When I transferred over from Twitter to NVIDIA, I had no second thoughts. That was such a no-brainer.

At NVIDIA, I also operated as an entrepreneur in some sense because we created this project called Rapids which is NVIDIA's open-source data sense platform. We ran it as a startup.

I left NVIDIA and took a 3+ month break. I started a company in that timeframe, and I thought that that was what I was going to do. The company was focused on trying to automate the whole process of building data sets for the training of AI agents. It's one of our largest fundamental problems right now that need to be solved at scale.

The creation of datasets is the most impactful thing to train great-quality AI.

Evan: A lot of startups are trying to do that or say they're doing that, Clément. I guess you're saying that it's still not being done well.

Clément: It's an extremely hard problem. Arguably even for the great labs and companies like Open AI much of that process is manual today. A lot of humans are looking at the failure modes and deciding what to do next, which works to an extent. We're creating better and better AI like that but we've got to be able to do better.

I had a chat with Demis Hassabis, DeepMind's founder and CEO, a friend of mine. I worked for him 10+ years ago when I was still doing my Ph.D. before Madbits. I started describing where I was at, and what I was trying to solve, and he convinced me quickly that DeepMind has all these great technology components and on the cusp of building something even greater. I have such a great role as part of that!

If AI was not happening at this scale right now, I would probably be back to being a startup entrepreneur and figuring out what to build next.

I'm torn because I'm so in love with the technology and the fundamental principles of scaling AI technology, that I feel like doing it with these types of partners at that scale is where I need to be.

Evan: It sounds like it's a clear decision, but it's interesting that you dipped your toes back in the water. Maybe you had to do that to know whether or not that was the right next step. Sometimes we have to! Before I started LDV Capital, I started another project and invalidated it quickly. I probably didn't know I had to scratch that itch to make sure that it wasn't the right thing to do.

Clément: That's right. I could have built something on my own again. But then there's this huge trend coming now of the scaled foundation models, and I'm glad that there's a lot of the ecosystem now that's trying to reproduce that either in open source or with different strategies or producing more compact versions of that. I want to jump into this core problem.

Are large language models (LLMs) sufficient or are we going to need more and how do we get to the next step?

Evan: What are you going to be working on at DeepMind? What are the challenges you're excited to work on?

Clément: We have a lot of things that we're planning to do, but I don't want to discuss some of these things too early.

LLMs are a key part of the puzzle. We call them LLMs now, they're just scaled neural networks with this great transformer-based architecture that treats input streams as tokens. These models have demonstrated that being trained on a huge amount of text data, they're able to build an internal model of the world that's satisfying and that can be used to query them. That's impressive!

We have lots of unsolved problems. We need to build something that's more cohesive, complete, and capable of getting close to AGI. We're going to spend the next 3-5-10 years (I don't know how long it's going to take us) exploring the rest of the space.

Evan: How does the researcher, the Ph.D., make the right decision to either start a business or go to a big company?

Clément: It's such a personal decision! You get input from people, it's good to get advice, and it's good to have mentors. But at the end of the day, you make your own decisions, and it's important that you make them based on principles that apply to you.

Evan: It seems like many deep technical researchers feel like it's almost binary. You have one choice or another. I see it as an iterative process. We have a lot of different chapters in our career, but I don't know, because I'm not a researcher or an engineer, I just collaborate with them a lot. What do you think about that?

Clément: It's true. When you are younger, 20+, you're getting out of school, you feel like the decisions you are going to make are going to define your entire career, and it's not true at all. We live in a world that's so dynamic and you can experiment so much! You can go in 3-5 year chunks. It's important to do a lot of everything!

When I started my company, I had no experience in big tech. Now that I do, I feel like I would be a much stronger young entrepreneur because I understand some of the ways these large organizations work and the true state of technology.

When you get out of grad school, you're naive but it’s also your strength because you don't know what you don't know. That pushes you to do things that are a little crazy.

For researchers specifically: do you want to work on fundamental research for a good chunk of your career? If the answer is yes, you should stick to it early on because it's hard to get back in. If you start moving into business and creating companies, you're never going to get back into fundamental research. That's an important decision.

If you're dancing around between applied research in an industrial context, or building products, you have so much freedom and you can go back and forth. You should be experimental.

Evan: What’s the biggest mistake you made as an entrepreneur?

Clément: I made 3-4 major mistakes. One of them was giving away too much equity early on.

Evan: To founders or to investors?

Clément: Investors. I was naive, I didn't fully understand the next steps. 10-15 years ago, there was much less street knowledge around the whole fundraising process from Seed to Series A. Now it's so codified that folks have a lot to read. Back then, it was harder. We guessed a lot and I did some things that put us in a situation where it was better for me to exit early than try to build it out. If I hadn't made that mistake, I would probably have tried harder.

Evan: What do you think is the best and worst trait of an entrepreneur?

Clément: The worst trait is ego. The best trait is grift.

Evan: What visual technologies are you most excited to finally appear or exist in 20 years?

Clément: I spent the past 6 years building the core technology for self-driving cars. We made tremendous progress there! On this topic, I'm going to agree with what you said earlier, this field moved way slower than anticipated.

Evan: It's true but isn't it because of human nature versus automobiles? The technology is there, but the automation is not.

Clément: In some sense, driving a vehicle has such a safety challenge that it's almost an AGI problem, where you would want to have an agenda that can fully understand, have a great world model of everything that surrounds it and can reason about it in ways that are similar to the way we do it.

Today, we're still brute forcing a lot of these layers. We've decomposed the problem and we're relying on the scale in neural nets to solve a lot of that problem, which works great, but it's not taking us to the finish line. Companies like Cruise and Waymo have solved this problem with this crazy expensive sensor platform. With the lidar, cameras, and radars building SD maps ahead of time, they can solve the problem in finite environments, like one neighborhood in Phoenix and one neighborhood in San Francisco, the cost to scale it to every other neighborhood in the world is insane. It's probably going to take us more than a decade to get there.

In the meantime, we're going to have cracked some more fundamental pieces of that AGI puzzle so that we can get to true world models. Something that's as good as LLMs, but for the visual world. Then we’ll start leaning on that to solve the problem.

LLMs got faster, but keep in mind that they do have the same type of boundary conditions problems where you could not deploy an LLM today in a safety-type environment. There's too much unknown! They're going to do things that are bullshit sometimes and you don't know it.

Evan: What's one last piece of advice for researchers that want to build businesses? Aside from going to LDV.

Clément: Talk to Evan for sure. He's a great guy!

The main advice is probably the one I gave to myself back then: find someone who loves building products, has an amazing product sensibility, and is obsessed with that thing that is going to delight customers.

Neural nets helped a lot of companies like Open AI and DeepMind, but when you build a company, you have to build a product that people are in love with. Finding a partner like that is the key thing.

Hope you enjoyed this fireside chat as much as we did. Check out other sessions too!

Here’s what Clement said about our 9th Annual LDV Vision Summit: "LDV Vision Summit was a blast this year, it's always great to hear from all the great entrepreneurs in LDV's network live. Also love that the LDV team drives discussions on all aspects of building companies, from fundamental science to leadership, team building, current trends, and history to better deal with the future. Highly recommend it!"